Paintings

Sylvia drew from a young age. As she wrote years later, she was ‘constantly drawing things – not things seen, always things imagined.’

THE PAINTINGS and illustrations of both William Morris and Walter Crane which she saw as a child had a strong influence on Sylvia. Aged 16 years old and in the same year her beloved father died, Sylvia won a free place at the Manchester School of Art where despite missing lessons through neuralgia she excelled under the supportive teachers. She won a host of awards including a travel bursary which enabled her to study in Venice in summer 1902. Here she copied Byzantine mosaics in St. Mark’s Cathedral and other religious works which may have influenced her later suffragette designs which feature angel-type figures in flowing medieval robes. Sylvia also painted several street scenes in watercolours, gouache or oil.

On returning to Manchester in spring 1903 Sylvia found her mother, Emmeline, had secured a commission for her to decorate a hall the Independent Labour Party (ILP) had built in Salford and named after Richard Pankhurst. This was to have dramatic if unintended consequences.

While undertaking the painting of the wall murals, Sylvia discovered the ILP would not admit women to its new social hall, something common at the time. Emmeline was outraged and with several other women founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in October 1903. Initially intended to secure justice for women in the Labour movement it soon grew into an independent movement.

Sylvia then gained a 2-year scholarship (with the distinction of having the highest grades of any candidate), to study at the prestigious Royal College of Art (RCA) in South Kensington, London between 1904 and 1906. Here she found that women were discriminated against in the allocation of paid scholarships or prizes. In 1905 Sylvia persuaded the family friend the Independent Labour Party MP Keir Hardie to bring this up in the House of Commons. At Parliamentary Question Time, he was told that of a total of 16 scholarships at the RCA each year, only 3 were awarded to women and the authorities ‘did not contemplate any change’.

Sylvia’s life as an art student in London was a struggle in some ways as it was for those with limited monies and away from home, although she recognised that she was privileged. She had become involved in the WSPU during 1905 and when she finished her scholarship at the RCA the following year she saw no way to support herself as a student to complete the five-year course so as to take the full diploma. There were limited opportunities for women to undertake art and she struggled how to balance being an artist, earning a living and playing a part in improving society.

These conflicts were partly reconciled by her artistic works for the WSPU over the next 6 years. Although hundreds, if not thousands of (mostly) female artists, designers and craftworkers contributed to the visual identity of myriad suffrage and suffragette groups, Sylvia’s designs were particularly striking.

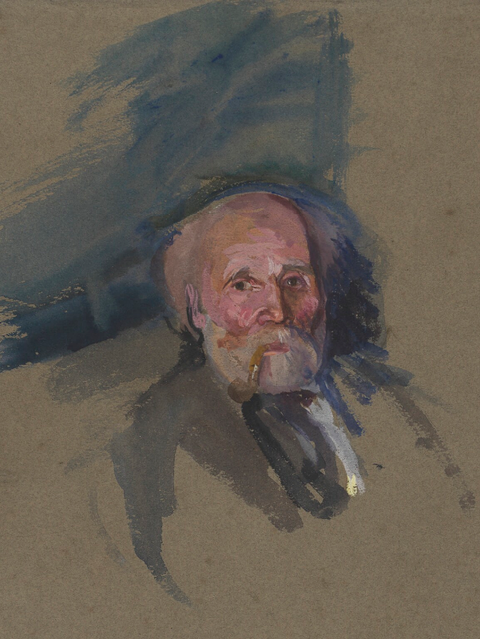

In summer 1907, Sylvia undertook a tour of the Midlands, northern England, and Scotland to see for herself the conditions of working women and paint them. Apart from her designs for the WSPU, these paintings are the highlight of her artistic career. Featuring unsentimental portraits of strong, dignified working-class women who were labouring in demanding physical jobs, they offer a unique insight into a large section of the population who were usually ignored. It is fitting that some of these works are today in the Palace of Westminster art collection and Tate, recognised as important of their type.

In summer 1910, during a lull in activity, Sylvia travelled with fellow suffragette Annie Kenney, to Austria and southern Germany as the guest of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, one of the key financial supporters of the WSPU and friend of Sylvia. On this holiday Sylvia made many sketches and drawings of local life including of the famous ‘Passion Play’ of the life of Christ held at Oberammergau. Some of these drawings were sold at auction in 2012.

By 1912, however, her political campaigning had overtaken her artistic career. Looking back in 1959 Sylvia wrote: “I found so much distress among the women of the East End of London that I felt I had to do what I could to help them, and that I could not yet return to my beloved profession.” As her work as an artist ended, her work as a lifelong campaigner began.

Women Workers of England

BY JACQUELINE MULHALLEN

For the rest of her life Sylvia remained constantly active, campaigning against political oppression and promoting worldwide human rights.

IN SUMMER 1907 Sylvia Pankhurst set off on a tour of the Midlands, the north of England and Scotland to make paintings and write articles about the harsh condition of women workers in industry and agriculture.

She stayed with local people and painted quickly using gouache, a type of water-based opaque paint. As her son, Richard, remarked in his book Sylvia Pankhurst – Artist and Crusader (1979): ‘She travelled as an artist and writer intent on recording significant details about working people, and sought to do with sympathy, but without sentimentality, rhetoric or invective’. These paintings were presented as ‘Women Workers of England’.

Although interrupted by requests to support the Women’s Social and Political Union at by-elections, she continued this tour until Christmas 1907. Cradley Heath, Staffordshire was her first stop, where the women worked making nails and chains with average earnings at five shillings a week, not allowed to take the more highly skilled work. Sylvia described it as a ‘blighted countryside’ with ‘a hideous disregard of elementary decencies in housing and sanitation’. At Leicester, the industry which employed women was shoe and boot making. She commented on the monotony of this: ‘always toecaps’. Ironically, the comment of the women watching Sylvia paint was, ‘I should never have the patience to do it’.

Sylvia painted the women working in the coal industry at the pit brow in Wigan. The bankswomen earned less than half what men did for the same job. When the coaltubs came to the surface in the cage from the pits, they entered the cage, dragged the tubs out and gave them a push to send them rolling off along the railway lines. The ‘pit brow lassies’ met the tubs and pushed, dragged and guided them on their way to the sorting screens, long belts which moved continuously and carried the coal with them, turning the points and pushing them towards the receiver where they were emptied. On either side of the sorting screens, rows of women picked out pieces of stone, wood and other waste stuff and removed what stuck to the coal, sometimes with their fingers. At the Potteries around Stoke-on-Trent, Sylvia made paintings and drawings of women working in the pottery industry, where they were debarred from more highly skilled jobs but turned the wheels for men throwers, trod the lathe for men turners earning very low wages. Lead colic, jaundice and lead paralysis were among the industrial diseases here and stillborn babies or ones who died soon after birth were common. The use of lead glaze for the ceramics saved fuel and manufacturers seemed to ignore the human cost.

When Sylvia went to Scarborough, she was pleased that the Scottish women, who moved along the east coast in the wake of the herrings, appeared to have a healthier outdoor life, singing and chattering over the fish they cleaned and packed into barrels. At Berwick, half the farm hands were women, ‘stooking’ or setting up the sheaves which had been left lying on the ground by the reapers (men), threshing in the barns, making straw ropes, loading produce on a cart. Her final stop was at a Glasgow cotton mill, where she made a number of paintings of the women workers but found the spinning room so hot she almost fainted. The operatives told her they were all made sick by the heat and bad air at first. The ring-spinning room where the children worked was the worst of all.

Sylvia’s impressions were recorded in a series of articles between 1908 and 1911 for the suffragette magazine Votes for Women and in her book The Suffragette Movement (1931) which Richard Pankhurst drew upon for his book Sylvia Pankhurst - Artist and Crusader (1979) in which he reproduced some of her paintings and drawings. There is a possibility that many more are extant. Richard remarks that none of the paintings survive from Cradley Heath, where Sylvia went out to paint every day, but in 1991, I found a copy of The London Magazine, 1908, which accompanied an article by Sylvia with reproductions of several of her paintings not included in any known collection. The frontispiece was a full colour reproduction of a chain maker at work. The others, in black and white, included pit brow lassies, shoemakers, a nailmaker and a cotton spinner. The price and the content of the magazine suggest it was intended for a middle-class readership and it is possible that readers bought the paintings. If so, it would be wonderful to know where they are.

Jacqueline Mulhallen is a writer with a special interest in Sylvia Pankhurst. In 1987 she co-founded Lynx Theatre and Poetry to tour a play written and performed by herself about Sylvia, which is still being performed www.lynxtheatreandpoetry.org

Campaigning Art

Sylvia’s artwork and imagery gave the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) its coherent visual identity between 1906 and 1912.

The WSPU was one of the first campaigning organisations ever to use design and colour to create a corporate identity. Although Sylvia was not the only artist involved, she designed flags, banners and fundraising items and used her artistic skills to decorate rooms for campaign exhibitions and meetings.

Sylvia’s Artworks in Museums

Most of Sylvia’s paintings are still owned by the Pankhurst family or are in unknown private collections with only a small number in public museums. Several museums, however, have examples of objects which feature Sylvia’s designs for the WSPU. Go to ‘Resources’ chapter